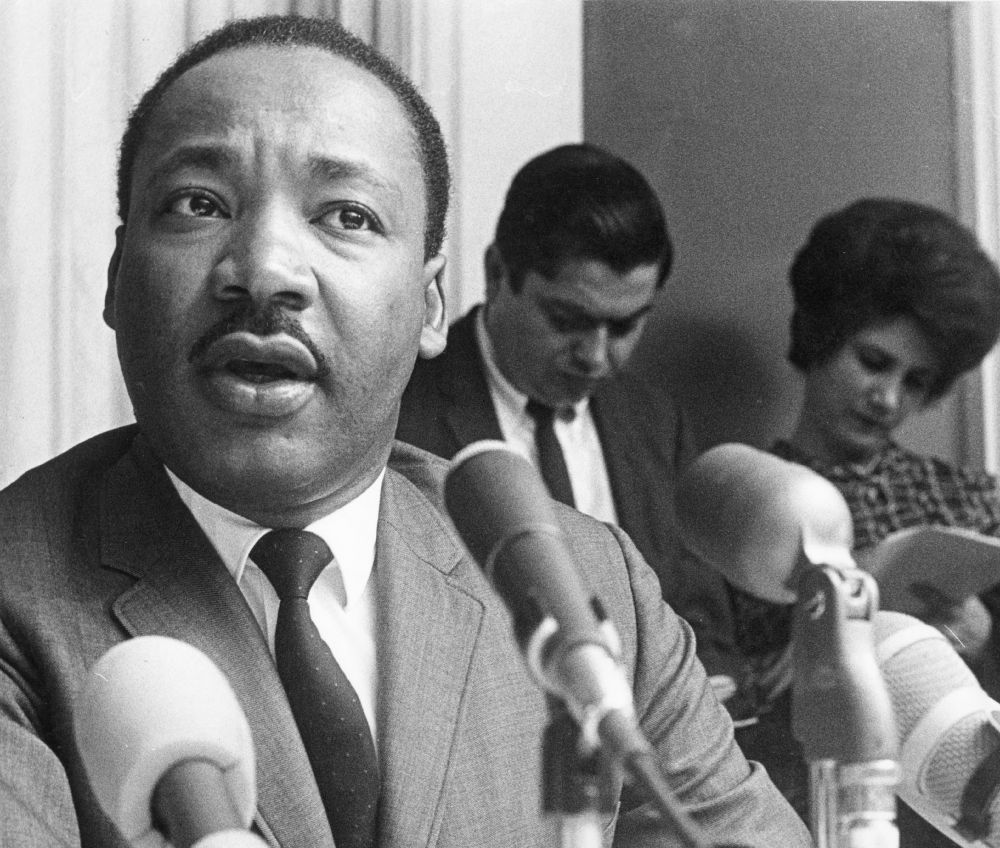

In the final years of his life, Martin Luther King Jr’s legacy was already cemented with his leadership in the Civil Rights Movement, the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

But one key element in civil rights was still missing in his view: housing justice. In 1966, King and his family moved into the impoverished Chicago neighborhood of Lawndale, and alongside Chicago activists, worked to dismantle unfair housing policies that barred Black residents from living in predominately White, middle-class neighborhoods in that city and others across the United States. It became known as the Chicago Freedom Movement, and it laid the groundwork for the Fair Housing Act passed two years later in 1968, one week after King’s assassination.

The Chicago Freedom Movement was a collaborative effort by King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the locally based Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO). The local activists invited King, and his message of nonviolence, to come to Chicago, which was touted at the time as the nation’s most segregated city.

The movement in Chicago sprung from concerns over Black children’s education, but soon King and others saw the problems afflicting the school system as symptomatic of broader issues: the lack of access to opportunity, financial instability, and their roots in unsafe and overcrowded housing. Together, they worked to raise awareness of the poor housing conditions forced upon segregated Black Chicago residents, and called for a policy of “open housing,” which would end segregation and let Black residents buy homes in any area of the city. With better housing came access to quality schools, better employment opportunities and financial stability.

The obstacles were many, common, and nationwide. In addition to policies of redlining, which deemed Black neighborhoods as undesirable for investment, covenant restrictions outright barred Black residents from swathes of the city, and mortgage lenders refused to lend to Black households looking to buy in White neighborhoods. Black homebuyers were at the mercy of exploitive contract sales laden with high risks but none of the security or equity benefits of homeownership, and often with mortgages well above the value of the home. As a result, many Black homeowners lost their homes and investments, and gained only crippling debt in return.

King’s own experience living in Lawndale, as he wrote in his autobiography, exposed him to the “emotional and environmental deprivation” poor housing took on the families and children living there— including his own. The words echo the challenges many people in substandard housing still face today:

“The slum of Lawndale was truly an island of poverty in the midst of an ocean of plenty. Chicago boasted the highest per capita income of any city in the world, but you would never believe it looking out of the windows of my apartment in the slum of Lawndale. From this vantage point you saw only hundreds of children playing in the streets. You saw the light of intelligence glowing in their beautiful dark eyes. Then you realized their overwhelming joy because someone had simply stopped to say hello; for they lived in a world where even their parents were often forced to ignore them. In the tight squeeze of economic pressure, their mothers and fathers both had to work; indeed, more often than not, the father will hold two jobs, one in the day and another at night. With the long distances ghetto parents had to travel to work and the emotional exhaustion that comes from the daily struggle to survive in a hostile world, they were left with too little time or energy to attend to the emotional needs of their growing children.”

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr., edited by Clayborne Carson

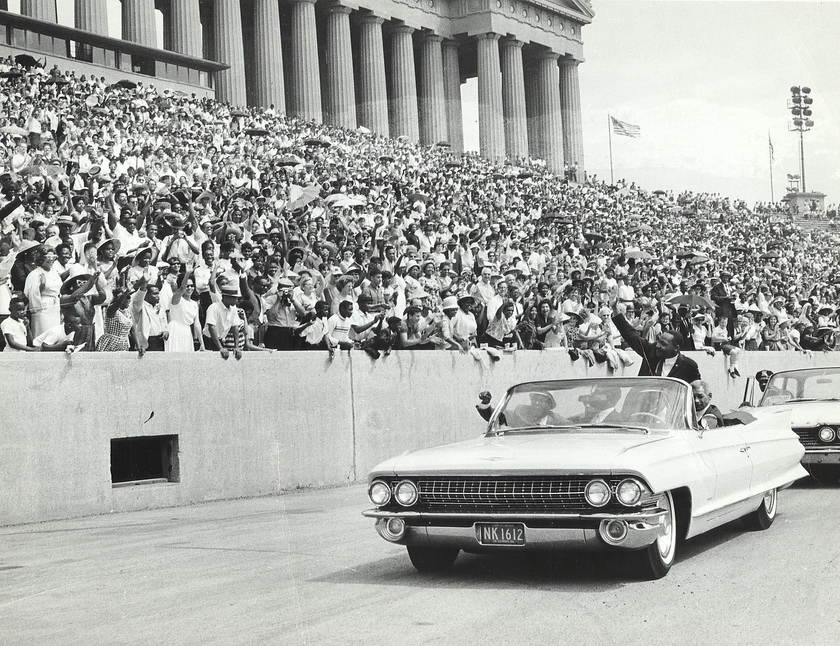

The Chicago Freedom Movement organized non-violent rallies, marches, and boycotts calling for fair housing, and in turn faced an onslaught of opposition. On July 10, 1966, an estimated 30,000 people listened as King spoke on housing justice at Soldier Field, a day known as “Freedom Sunday.” But actions in public were met with racially fueled anger and violence. The violence reached a peak at a march in August in the all-White neighborhood of Marquette Park where marchers were pelted with bottles, rocks, and bricks. King himself was hit, prompting him to remark later: “I’ve been in many demonstrations all across the South, but I can say that I have never seen, even in Mississippi and Alabama, mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I’m seeing in Chicago.”

To avoid more violent confrontations, King, tenants, and other activists met with Mayor Richard Daley and city officials to discuss a solution. What resulted was a Summit Agreement that included the creation of Chicago’s Leadership Council for Metropolitan Open Communities. The council was charged with monitoring and advocating for fair and open housing practices in the city, with a particular focus on homeownership opportunities.

While promises of more public housing and open lending practices went unfulfilled, and despite the city’s lack of will for legal enforcement, over time the Leadership Council set an example for training, site tests, research, and direct service to create more equal housing opportunities for Black Chicagoans. Reflecting on an ancient proverb, King called the Summit Agreement “the first step in a 1,000-mile journey.”

The larger impact, though, was the message the Chicago campaign sent across the country — that intrenched policies of racial discrimination and segregation in housing had to end. Like the cities of Birmingham and Selma, Alabama, years before, Chicago became King’s fulcrum for a housing justice revolution. It would be two more years before that revolution would take hold. The Chicago Freedom Movement is credited for inspiring the federal Fair Housing Act, which in 1966-67 languished in Congressional gridlock. Upon the news of King’s assassination in April 1968, President Lyndon Johnson pushed forward the passage of the Act in Congress, and one week after King’s death, signed the bill into law.

The Act prohibits housing discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin, sex (later amended to include gender identity and sexual orientation), disability, and familial status.

The Chicago Freedom Movement established housing justice as integral to civil rights, and the work to live up to its potential — the 1,000-mile journey — continues today. In 2006, financial pressures forced Chicago’s Leadership Council to disband, even as it acknowledged that the call to action championed by King and others in the movement remained unfinished. Despite laws against such activities, redlining and other racially discriminatory practices persist.

Today, the nationwide homeownership rate among Black Americans is about 45 percent, still 30 percent below their White counterparts, the same as it was when Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act into law 55 years ago.

Habitat recognizes the systemic inequalities that decades of racial injustice have caused and works to help more individuals and families achieve the stability of homeownership. We believe everyone deserves a safe and affordable place to call home, and celebrate the work and mission of Martin Luther King, Jr., to create an environment across the country where housing justice can take hold.

Selected Resources:

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr., edited by Clayborne Carson.

The Chicago Freedom Movement: Martin Luther King Jr. and civil rights activism in the north

The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University.