This article is part of a series of race and housing in Portland. Read parts one and two here.

In May of 1948, a hastily built wartime housing development called Vanport, Oregon was suddenly flooded, forcing the evacuation and relocation of over 20,000 people, many of whom were Black. In an instant, the City was forced to reckon with a massive wave of local migration and the settlement of Black families at a time of racism and deep prejudice. The decades following the flood mark by an era of advancement for the Black community in Portland. Then it was quickly followed by a string of racist housing policies that uprooted entire communities of color.

The demographic shifts in our region following the flood reflect not just a community in retreat and relocation, but an intentional set of housing strategies designed to push People of Color into small tracts of cheap, underdeveloped land. This is the path through which Portland was formally segregated.

The bait was the promise of homeownership. The switch wouldn’t come until years later, when city officials exploited the tool of eminent domain under the guise of urban renewal—effectively decimating a generation of Black wealth-building in Portland.

The GI Bill

When troops returned from their posts overseas, they came home to a new set of federal initiatives, which aimed to provide economic aid to veterans and prevent a wave of postwar unemployment. The GI Bill, which was touted as a civil rights achievement nationally, provided veterans with tuition assistance, unemployment insurance, vocational placement, and, importantly, home loan opportunities. On its face, the Bill was groundbreaking and unprecedented for working-class families. In Portland, it helped establish Portland State University.

The problem with the Bill was that the majority of the legislation was to be implemented by states and local municipalities—which had more prejudice written into laws and codes than federal statutes. In effect, it is what propelled millions of White servicemen into the middle-class; it’s also what kept a disproportionate number of Black veterans bound to generations of poverty.

Redlining in Portland

In its implementation, the guarantee of home loans to veterans created the concept of the suburbs. Suddenly, millions of families were able to buy a home for the very first time. However, the Federal Housing Administration’s guidelines for distributing loan opportunities relied on explicitly racist standards that made it virtually impossible for people of color to purchase a home, even during an economic boom.

For most White veterans and first-time homebuyers, the Federal Housing Administration was a blessing. The new initiative subsidized mass-construction efforts of single-family homes while also insuring and underwriting the mortgages with which buyers bought the homes they were to own.

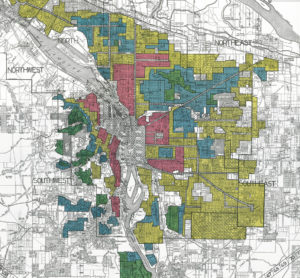

In working with private lenders and local municipalities, the federal government established a process of rating the safety of loans they were guaranteeing all over the nation. The rating system created was based upon geographic, economic, and, racial measures. The scheme gave neighborhood ratings of either Type A, B, C, or D. These ratings were then used to determine if private lenders would offer loans and if the federal government would insure them.

This rating system was then laid out in color-coded maps that made it easy for banks to efficiently approve or reject applicants based on the location of the property. The neighborhoods with the lowest ratings were shaded in red, subscribing the term redlining that plagued Black populations for generations. In Portland, this era of segregation is seen in the red shading covering over Albina, Inner-South East, and Downtown where the largest populations of Black families lived.

Because of this practice of denying loan applications in predominantly White neighborhoods, many Black families were forced to rent, preventing them from offering future generations the wealth-building opportunities that homeownership secures. Those that were able to purchase a home in the relegated, redlined districts were often subjected to extremely high interest rates and predatory lending practices that made foreclosures likelier and intimidation all but certain.

White Flight in the Albina District

The Black population has never exceeded 7% of Portland’s total demographic makeup. Before the war, half of Portland’s Black communities lived in Albina. According to a report by Dr. Karen Gibson of Portland State University, in the 1950s, “Albina lost one-third of its population and experienced significant racial turnover as White residents left en masse for the suburbs and Black residents moved into Albina from temporary war housing.” During this time, White families benefited from fleeing to neighborhoods with better FHA ratings, lower interest rates, and where projections of home values showed growth. By 1960, 80% of Black Portlanders lived in Albina. According to Dr. Gibson’s research, by 1960 “there were 23,000 fewer White and 7,300 more Black residents” in the small 4.3 square-mile district. Yet, for all of this blatant segregation, it wasn’t until the following decades that the City’s vision became clear.

Progress in Albina

In this historical context of institutionalized racism, it is difficult to imagine that the subsequent era of Portland’s housing practices would be much better for people of color. Yet in the interim years, Portland’s Black community showed signs of real progress, even prosperity. In the late 40s and early 50s, the Albina Neighborhood generated many new Black-owned businesses that formed the hub of Black life in Portland. From medical offices, jazz clubs, barbershops, and grocery stores, Black-owned businesses lined the streets at Albina’s core intersection of Russell and Williams. Homeownership was rising for many living in the area as new vacancies opened the chance to own property. Passage of the 1953 Public Accommodations Bill in the state legislature furthered the prosperity and progress for Albina’s People of Color.

Yet, with virtually no public investment, much of the infrastructure of the small, overcrowded district began dilapidating. This led to many investors in local planning circles to view Albina as the perfect tract of land to build massive infrastructure projects that were just voted in as public bonds. Again, a sudden shift through the gains of many Black residents was in jeopardy. The term Urban Renewal came to be known as both a sign of local progress and a heavy, destructive force. While the projects that commenced around this time gave Portland it’s most recognized monuments, it also wiped out an entire generation of Black progress.

Urban Renewal and Eminent Domain

With cheap land, high crime, and relatively little political power, Albina stood as an easy prey for eminent domain to provide land for projects like the Memorial Coliseum, Interstate-5 and Highway 99, PPS’s district offices, Portland’s Water Bureau, and eventually the Emmanuel Hospital Project. When funding lined up for each of these projects, the City was quick to designate as many tracts of Albina’s cheap land as “blighted” making it institutionally easier to rezone it for demolition and commercial investment.

Over 1,100 homes in Albina were demolished during this time—the overwhelming majority were Black homeowners. The renewal projects resulted in yet another major exodus of Black families. From the Lower Albina Neighborhoods of Boise and Elliot, many relocated to the Upper Peninsula and N. Portland where redlining continued to limit homeownership opportunities.

Subsequent Damage to North Portland

The effects of this era of redlining and renewal is seen in North Portland’s economic hardship, high crime rates, and absentee landlordism of the 80s and 90s. As Dr. Gibson states, “Albina hit rock bottom in the 1980s.” The preceding actions decimated the population gains that earlier made Black-owned businesses profitable for the region, and with that, the housing market simply collapsed. From WWII to the 1980s, Albina’s total population dropped by 27,000. Home values at this time dropped to 58 percent of the city’s median.

Absentee-landlordism became a new normal for the region, whose shrinking population saw little gain from the economic boom of the 80s and 90s. Previous decades of redlining made homeownership impossible for many Black families, who were then forced to rent from many White absentee-landlords who charged exorbitant rates and neglected proper upkeep, seeing any investment as wasteful. By the late-80s, fewer than 44% of Albina homes were owner-occupied.

The practice of predatory lending added fuel to an already bad situation—as conventional banks refused to approve loans in the region, predatory lenders would buy low, sell high, and charge interest rates that often resulted in foreclosure. Because of these disparate housing strategies, we saw North Portland of the 80s and 90s continually scarred by abandoned houses, a crack epidemic, gang activity, and continued migration.

The Legacy of Urban Renewal

What began as a sudden and emergency migration morphed into both progress and destruction for Black people living in Portland in the years between 1950 and 2000. Local housing policies preceding and during these 50 years help explain the disparities we still see haunting many of our communities of color. From employment, education, and public health statistics, we see the history of these policies living as a potent and painful reminder.

It also helps explain why, in 2020, we see such a drastic gap in homeownership rates between White people and people of color. To this day, there remains a 32% gap in homeownership between White and Black Portlanders. That represents a total of 4,200 Black-led households who do not own the home they live in as a result 150 years of redlines, neglect, eminent domain, under-investment, and outright racism.

– – – – – – –

This article is part of a series outlining the racist housing practices that have pervaded in Portland’s neighborhoods for over a century. Part IV features how the Great Recession affected Black homeownership in Portland, the consequences of gentrification, the City’s efforts to make up for a century of mistreatment, and what can be done about the City’s current racial gap in homeownership.

Sources:

Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment, 1940-2000 by Karen J. Gibson

City of Portland Civic Planning, Development & Public Works, 1851-1965: A Historic Context

A ‘Forgotten History’ Of How The U.S. Government Segregated America By Terry Gross