This article is part of a series of race and housing in Portland. Read parts one and two and three here.

Since the 1990s, no area in Portland has experienced such dramatic change than in North and Northeast neighborhoods. From vacant buildings and declining home values, the region that encompasses the historically Black neighborhoods of Elliot, Mississippi, Williams, and Woodlawn has become nearly unrecognizable in just the span of a single generation. In the past 30 years, White settlement in the area has exploded, increasing the costs of living for everyone living there. For long-time residents, seeing this transformation and influx of wealth has been something of a mixed bag.

Prosperity and Exploitation

Although North Portland was an economic desert in the 80s, the same cannot be said of the cultural roots that thrived despite under-investment, particularly in the Black community. But by the mid-90s, things began to change. The influx of capital to the region, (mostly White, outside money) cut through life as only a double-edge sword could do. At one end, there was mass investment in the local housing stock, which increased home values to most homeowners. At the other end, this influx of capital flowed mostly to White proprietors and new-entrants, leaving Black renters entirely priced out. This inversion of capital also helped White businesses grow, while Black businesses, facing a declining population, folded. Those early investments mean North Portland now enjoys more small businesses, lower crime rates, and better funding for schools and community services–but at a cost to the Black community that once thrived there. These benefits continue to largely exclude those who helped to establish the community. By the late-90s, the entry of White residents surpassed Black residents. The consequence is an equation that has made Black homeownership, entrepreneurship, and survival exceptionally difficult for the few who chose to stay.

One thing is clear: the incremental draining of Black wealth paid the way for the region’s progress and prosperity.

Gentrification Reflected in Housing Market

With cheap land to build, increased investment of public dollars, changes in zoning codes, and a vast supply of empty, Victorian-style houses, people from across the country and within Portland flocked to the region in the 90s. Home values in the Elliot, Irvington, King-Sabin, Boise, and Woodlawn Neighborhoods quadrupled in just 10 years from 1990 to 2000. For the vast majority of Black residents in the region who rented, the sudden surge in home prices essentially barred them from ever being able to purchase a home in the neighborhoods where they grew up.

The fact was that in the 1990s, many factors contributed to the rise in home prices. The City created an abandoned housing task force, the Portland Development Commission invested heavily to transform abandoned homes into owner-occupied units, and the booming economy made nearly every other area in Portland unaffordable to most middle-income White families and out of reach for even more Black families. Karen Gibson of Portland State University summarized this transformation as a mixture of contributing factors that generated a perfect storm, helping rise the tide of White homeownership and simultaneously draining the city’s share of Black homeowners.

A booming economy, cheap mortgage money, bargain-basement property, and pent-up demand coincided to transform pockets of Albina in three or four years from very affordable to out of reach. At the beginning of the decade, the worry was abandonment; at the end, it was the preservation of affordable housing. This cocktail of circumstance had the impact of decreasing Albina’s proportion of Black homeowners by 36% while growing White homeowners by more than 43% in just a decade. This inverse disparity reflects the simple and inherent bias in a market’s valuation of White property ownership over that of more diverse communities—effects which stem from a systematized pattern of discrimination in early housing practices.

Misleading Promise in Portland’s Homeownership Rates

In the 90s, Portland’s overall Black homeownership rate increased 4%–a figure that may seem like progress. However, the truth is more complicated than it suggests. The patterns of migration and rentership among Portland’s BIPOC communities have always been misleading. For instance, this 4-point increase in homeownership can be directly attributed to the simple fact that many renters fled. During this time, a large share of Black renters left North Portland in pursuit of cheaper rent, mostly east of Interstate-205. So while the share of Black homeowners increased, the real number actually plummeted during this era of “progress.” Instead, progress flowed directly to White homeowners, who saw their homeownership rate surge from 44% to over 61% between 1990 and 2000.

The Great Recession

At the turn of the century, the few pockets of Portland’s affordable housing were quickly seized and evaporated. The housing boom of the early 2000s saw home values grow even higher in North Portland. Finally, it appeared that the economic boom of the 90s had caught up to benefit many people of color in our region. The Black community particularly gained significant ground by 2007 when it came to homeownership. Then, just as the trend was going upward, nearing 40% for the first times in decades, it suddenly and tragically reversed. Gains were lost, as was much hope.

Just as the Black community’s economic outlook began to grow to new heights, the subprime mortgage industry tanked, and with it, the world fell into the worst economic collapse since the Great Depression. Foreclosure data helps show just how fragile the perception of stability was for those in our region who needed homeownership the most. In the course of just a decade, the Black homeownership rate dropped to below 28% in Portland.

It turns out that many subprime lenders preyed upon North Portland’s communities of color for years, particularly in the Black community. From 2005 to 2008, the rate of foreclosures among recent borrowers was highest for Black families—effectively double what it was for White families. Nationally, over 8% of Black people lost their homes in the wake of the recession. This disproportionate effect highlights the nature of displacement on communities of color. North Portland for instance, saw a loss of over 7,600 Black residents in the years between 2000 and 2010. The overwhelming factor to this mass displacement was foreclosure.

City’s N/NE Preference Policy

During the recovery years following the Great Recession, the City began working with several leading community coalitions to develop a strategy for overcoming losses in homeownership, particularly for Black families. Beginning with Mayor Charlie Hales’ declaration of housing emergency in 2014, the initial vision for many community leaders was a plan that addressed the impacts that urban renewal, redlining, and racist lending policies had on Black homeownership. The result is now a $70 million investment known today as the North/Northeast Preference Policy.

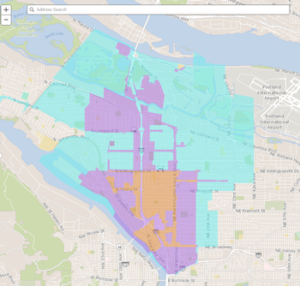

The policy’s aim is to repair the historic and ongoing displacement. The program gives priority and additional access to funding to housing and homeownership applicants who were displaced, are at risk of displacement, or who are descendants of households that were displaced due to urban renewal in three zones in North Portland. Habitat for Humanity Portland/Metro East is one of several Preference Policy partners that are working with the City to build homes in support of this effort. Currently, we are building 42 homes in two communities in the Kenton and Portsmouth neighborhoods that will be purchased by qualified Preference Policy applicants.

The Future of Black Homeownership

According to the City’s Housing Bureau and the US Census Bureau estimates, the Black homeownership rate in Portland is currently at 25%. This is the lowest it has been in more than a century. Compared to a White homeownership rate of over 57%, this translates to a gap of at least 4,279 Black-owned homes. In fact, if Portland had a truly equitable homeownership rate among all racial groups, there would be 11,538 more owner-occupied units among people of color. This is an incredibly challenging problem and the solution will require bold innovation and heavy investment. It will demand all levels of government, every local housing organization, and many more individuals join in to solve it.

In the first part of this series, we covered the early history of housing discrimination in Portland, understanding how early racism in the state’s founding transferred to an era of redlining and de facto segregation. Part two focused on how North Portland became a hub of Black life during WWII and how Vanport’s flooding laid the foundation for the City to declare much of Albina as “blighted” and prepared for demolition. The third installment highlighted the decimation that Urban Renewal had on North Portland and how that contributed to a diminishing homeownership rate for Black Portlanders. This article told the story of brief gain, and quick loss as represented by a declining homeownership rate after the Great Recession. With such a problematic history of housing and racial discrimination, it is clear to see how current disparities came to be and how they’ve continued to last even today.

To close the racial gap in homeownership, it will likely cost billions and take years, even decades, but the alternative of doing nothing and letting this long history of discrimination speak for our future is not an option. We cannot do nothing and watch as yet another generation of Black Americans are barred from the most tangible feature of the American Dream—owning a home.

– – –

Sources:

Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment, 1940-2000 by Karen J. Gibson

Foreclosures by Race and Ethnicity: The Demographics of a Crisis by the Center for Responsible Lending

Home Ownership Rate for Black Portlanders and Black Oregonians Has Plummeted by Nigel Jaquiss

2019 State of Housing Report by the City of Portland’s Housing Bureau

Fewer Blacks own keys to a Home by Steve Law