Just steps beyond Jackie Jones’ front window are the homes she always longed for. A place of her own, that she could take care of properly, in the Northeast Portland neighborhood she was raised in. She can see them from her rental home’s window, but they might as well be a hundred miles away.

It’s a common story for Portland: The once predominately Black — and affordable — neighborhood was becoming increasingly desirable with gentrification, housing prices escalated dramatically, Black families were priced out. White families moved in.

“There’s a lot of Caucasians that are moving into all of the houses that I wouldn’t be able to get into. And these guys are 20 years younger than me,” said Jones, now 60, who is Black. “I’m like, how’s this happening? I can’t even get this house.”

This house is a declining rental she’s lived in for 20 years. She wanted to own her own home but came up against familiar barriers: She was told her credit wasn’t good enough, so she worked to improve it. She was told she didn’t make enough money, even though she has been employed as a teacher for decades, and she was told she had to settle for a less expensive home outside of the city, away from the neighborhood she’s lived in all her life. She also had a family and needed a home big enough for herself and two of her children.

Jones said she isn’t sure if her barriers to homeownership were because of her credit or her race. “I just know it was hard for me to get into a home versus other people,” Jones said.

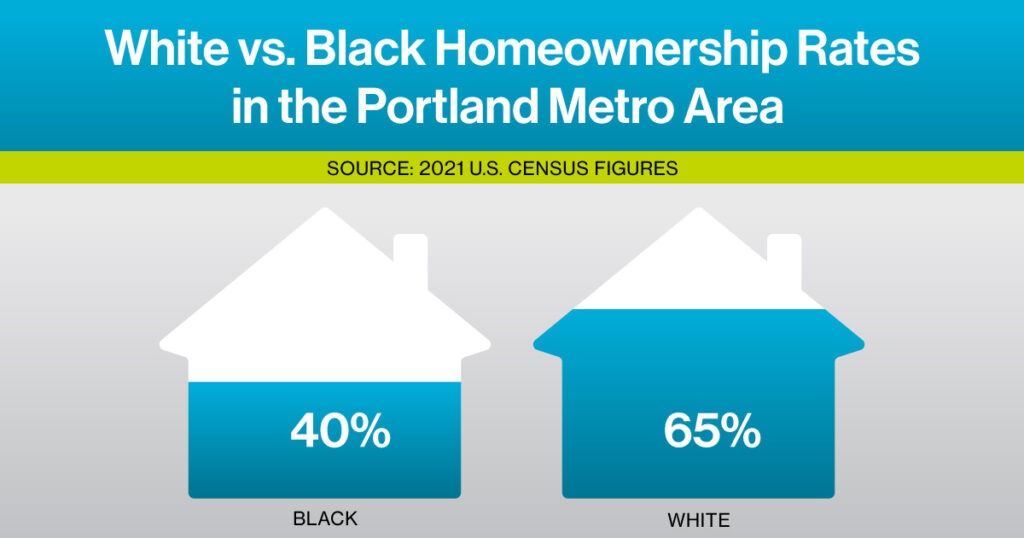

So, like 60 percent of Portland’s Black population, she kept on renting.

Homeownership rates among people of color consistently fall well below that of their White counterparts. And the Black homeownership rate is consistently the lowest: 40 percent of Black residents in the Portland metro area are homeowners, according to 2021 Census figures, compared to more than 65 percent of White residents. That’s a 25 percent gap for 2021.

Nationally, at 30 percent, the gap between Black and White homeownership is as bad as it was in 1900, more than 100 years ago. That’s prior to anti-discrimination laws, including the Fair Housing Act of 1968 that technically prohibited redlining and lending discrimination, and changes to policies that systematically excluded Black Americans from homeownership and the social and financial stability it brought with it.

“With the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, all it really did was try to create a level playing field,” said Allan Lazo, executive director of the Fair Housing Council of Oregon. “It didn’t really redress the situation that had been caused by a much longer history of the oppression of Black community members, and then the explicit housing discrimination that those communities experience.”

The gap was exacerbated by the GI Bill, which in its implementation accelerated White homeownership, education, and wealth after World War II, and almost entirely excluded Black veterans from the same benefits.

“People want to find other reasons for why (the gap) can’t be closed. But the simple reason is, because we created it in the first place, and never did anything to fix it,” Lazo said. “So it has just persisted and perpetuated.”

What persists has been the study of numerous reports: The legacy of racial discrimination has led to generational poverty, underemployment, discriminatory lending policies and home devaluation, and ultimately the critical lack of access to credit and affordable mortgages.

And it has exacted a high toll that continues today. The financial institution Citi released a report in 2020 concluding that denied housing credit meant 770,000 fewer new Black homeowners over the past 20 years, at a staggering loss to the nation’s GDP of $218 billion.

“There are literally billions of dollars of Black wealth that gets erased in that systemic process. There’s an economic argument to say that inequality costs everyone. And I think that that’s one way we can look at it. The other is that it not only costs everyone, but it impacts everyone.” Allan Lazo.

The impact is the nation’s failure to deliver on its promise of freedom and equality, and where we are collectively in addressing that, according to Lazo.

“We’re very, very far from that promise,” Lazo said. “And if that’s a promise we’re going to continue to make as a community, as a culture, and as a country, we ought to be looking for ways to live up to that.”

Jackie Jones’ housing options changed when she began partnering with Habitat for Humanity. This year, Jackie will become a Habitat homeowner, and soon she’ll be moving into her new home in Southeast Portland. She said she’s incredibly grateful and happy for the move, especially for the stability it will provide her two youngest children.

“It would be their home, it would be theirs, and they won’t have to go out and try to apply for something and try to rent something and get turned down, everywhere they go,” Jones said. “I think this will be good for them.”

This school year Jones also got her own office, advancing to the role of education coordinator with Albina Early Head Start. She has worked there for 28 years.

In January, Gov. Tina Kotek announced her administration’s goal of reducing Oregon’s racial homeownership gap 20 percent by 2027. Doing that will mean reversing decades of forces that created it in the first place, including those we thought we ended many years ago.

Racist history looms large

Like many cities, Portland still bears the imprint of racist housing polices. Throughout the first half of the 1900s, lending institutions custom populated neighborhoods by how they administered credit and to whom they allowed loans. It was a process called redlining, so named for the red ink that delineated undesirable neighborhoods where loans were denied. Spacious neighborhoods, parks and infrastructure became the hallmark of preferred neighborhoods, held exclusively for White people by restrictive covenants that barred Black residents.

Discriminatory practices like these and many others segregated Portland’s Black population to underdeveloped areas in North and Northeast neighborhoods, most notably in the historically neglected Albina District. Comprising the Eliot, Boise, Humboldt, Overlook and Piedmont neighborhoods, Albina was also one of the few places where people displaced by the 1948 Vanport flood could afford to put down new roots.

The district was culturally rich, but financially and politically vulnerable. As Portland expanded, the cheap land and designated “blighted” areas of Albina were easy targets for eminent domain by the city. More than 1,000 affordable homes in the Albina District and surrounding area were demolished to make way for a series of projects starting in the 1950s.

Chronicled in a study by Portland State University, the list of homes destroyed is staggering:

- 80 dwellings destroyed in 1952 for the expansion of Interstate Avenue into Highway 99W.

- 235 dwellings cleared in the construction of Memorial Coliseum, which opened in 1960.

- 275 units destroyed in the creation of I-5, which opened in 1962.

- 300 units demolished in the Emanuel Hospital Expansion Project between 1962 and 1973, in what was considered the “Heart of Black Albina.”

Additional demolitions occurred to make way for the Kerby Avenue Fremont Bridge approaches to the new I-405, and 65 homes were taken to create the Portland Public School’s Blanchard Education Center, which opened in 1980.

While not all these lost homes were occupied by Black residents, the cumulative result on the Black community was devastating. Census figures show that by 1980, Black residents in the Albina District had plummeted more than 92% since 1960, according to the PSU study of the area.

The city’s actions are now the subject of a federal lawsuit brought by the families of former Albina residents seeking restitution for their displacement 50 years ago.

More than just a house

One of those homes lost in the I-5 expansion was the rental home of Camille Trummer’s grandmother. Trummer believes the structural and emotional circumstances of that loss contributed to the reason her grandmother never owned her own home, and one of the reasons her own mother bought a home as soon as she was financially able.

Growing up, Trummer doesn’t remember so much hearing about the wealth assets of homeownership, but rather the value of stability and the sense of home itself — something her mother longed for growing up and wanted to carry forth to her own children.

“Her greatest memory was going to her grandmother’s house,” Trummer said. “So, I think for my mother, she wanted to recreate this feeling of going to the same home, all the time, because she grew up moving a lot.”

A few years ago, Trummer bought her great-grandmother’s 1942 farmhouse in Northeast Portland’s Overlook Neighborhood, a move she said was made possible because of the equity from her previous Kenton home. She and her partner have rebuilt and redesigned the home, creating a more modern property for the couple and their two children.

The value and stability of homeownership is engrained in Trummer, who works as an interdisciplinary social impact consultant and has served as a policy advisor for the city of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. She’s also a passionate advocate for homeownership and serves on the board of directors for Portland Housing Center which helps people prepare for and reach their homeownership goals.

“My work as a strategist has always been around identifying the root causes and dismantling the systems that keep perpetuating the same outcomes,” Trummer said. “If we want folks to be more financially literate, then we need to be offering culturally specific accessible classes, affordable classes, free classes, if you ask me, for populations that have been disadvantaged for so long. And they need some time to catch up.”

Housing costs, minimum mortgage amounts and affordability

It’s not exactly news that Portland homes are expensive and getting more so every year. By the close of 2022, the median price of a home in Portland was more than $560,000, according to the online real estate aggregator Zillow.

But even up to the 1990s, homes in Northeast Portland could be had for $25,000 or less. However, minimum mortgage policies meant people wanting to buy affordable homes — for $15,000 to $17,000 in some cases — couldn’t get a loan. A series of articles in The Oregonian in 1990 outline numerous complaints from would-be homeowners in Black neighborhoods who were denied loans from multiple lending institutions for being less than the minimum loan amount, which commonly topped out at $40,000.

Without that community investment, homes in the Albina District went into decline, homes were bought up, often with cash from outside investors, and leased as rentals to turn a profit.

In recent decades, government-crafted incentives toward revitalization and urban renewal attracted speculators to the profits lying fallow in undervalued neighborhoods. Northeast and North Portland were systematically being gentrified. Lower-income residents, often people of color, were priced out of their own homes. Legacy businesses were shuttered, and new residents and companies moved in.

Portland’s Housing Bureau has for years strategized to reverse those negative impacts on Black homeownership with down-payment assistance loans and subsidized development of affordable homes for purchase. The vast majority — 95 percent — of households receiving homebuyer subsidies through PHB are people of color.

The city’s N/NE Preference Policy, launched in 2014, dedicated $5 million to creating approximately 65 first-time homebuyers who were longtime or displaced residents of North and Northeast Portland. Today, that funding amount has increased to nearly $14.5 million, with the goal to support up to 131 new homebuyers. Habitat for Humanity Portland Region works in partnership with the city’s Preference Policy to help program participants become homeowners.

While Portland’s Preference Policy doesn’t exclusively serve Black households, it does provide a tool to prioritize residents of the most impacted areas for homeownership opportunities.

The PHB also partners with culturally specific organizations to help encourage homeownership, and financial education programs to provide counseling services that improve credit ratings, lower debt, and increase savings.

Martha Calhoon, spokesperson with the Portland Housing Bureau, said these programs are working well to improve potential homebuyers’ ability to purchase, but rapid increases in home prices and rising interest rates continue to “move the goalposts” for prospective buyers and are additional barriers to closing the gap.

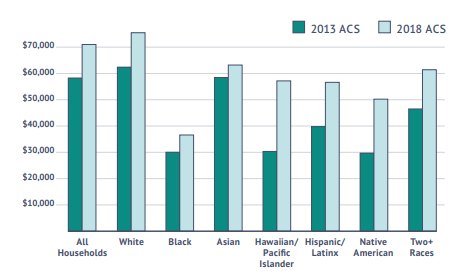

Income disparity is one of the main obstacles to overcoming the homeownership gap, said Calhoon. Factors such as rising interest and inflation rates, along with the COVID pandemic and ensuing economic crisis, make housing stability, economic opportunity, and homebuying options continually difficult, and they have a disproportionate impact on communities where these gaps already exist and only serve to deepen existing disparities. (See PHB graphic on income disparity)

“Income disparities in Portland are particularly steep among Black households and, even when we see economic gains, it is not enough to make up the gap,” said Calhoon.

Today, according to the Portland Housing Bureau, based on the median annual income of the average Black, Native American or Latinx family, not a single neighborhood in Portland is considered affordable.

Portland Median Household Income by Race and Ethnicity

National patterns of underinvestment and devaluation

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 made redlining illegal, but it never went away. As recently as this year, the Department of Justice has reached settlements with lending institutions across the country for discriminating against communities of color.

In 2015, the Department of Housing and Urban Development reached an historic $200 million settlement with Associated Bank following allegations that for years the bank engaged in racial discrimination and unlawful redlining by disproportionately denying loans to Black and Hispanic applicants. Similar settlements have been reached between banks and the Department of Justice.

If the loss in investments into Black homes and neighborhoods is one side of the coin, the devaluation of that investment is the other. Lower home values mean less income upon sale and affect an owner’s ability to refinance and borrow. Statistically, Black homeowners go into greater debt for less valuable homes and receive less of a return on homeownership than White owners.

Several news outlets have reported cases of Black homeowners receiving significantly higher appraised home values when they had a white person pose as the owner. In one case, the appraised value increased by nearly half a million dollars after a white person stood in for the Black homeowner and Black artwork and mementos were removed.

According to nationwide research by the Brookings Institute in 2018, homes of similar quality in neighborhoods with similar amenities were valued at 23 percent less, in majority Black neighborhoods, compared to those with very few or no Black residents. That’s $48,000 per home on average, amounting to $156 billion in cumulative losses.

State task force calls out solutions

In 2018, the Oregon State Legislature created the Joint Task Force on Addressing Racial Disparities in Homeownership, which identified a familiar list of barriers to homeownership for people of color. Topping the list was building and purchase costs, supply, and land use, and it also included credit issues, mortgage lending policies and the racial wealth gap.

In its final report released in October, the panel laid out recommendations for funding and organization capacity of homeownership organizations, institutional accountability and regulatory measures, and innovative models for homeownership financing and development.

Among those recommendations is additional funding for matched individual savings accounts for communities of color, additional support for down payment assistance and flex spending programs, and an ongoing $100 million budget to incentivize homeownership by subsidizing the development of 500 homes up to $200,000 each.

It also recommends racial and implicit bias training for mortgage and real estate professionals, which has become a bill now before the state senate’s Housing and Development Committee.

The recommendations echo the priorities set by Gov. Tina Kotek, to reach her administration’s goal of reducing the racial homeownership gap by 20 percent in the next five years. Kotek has specifically called out supporting community land trusts and shared equity homeownership programs, and promoting diverse housing types such as duplexes, triplexes, and quads.

Kotek’s plan also notes cracking down on discrimination by partnering with federal government and community organizations to enforce fair housing laws.

If Oregon succeeds in dramatically closing the homeownership gap, it will be bucking the national trend. According to a 2022 survey of new homebuyers by the National Realtors Association, 88 percent identified as White, 8 percent identified as Hispanic/Latino, and only 3 percent identified as Black or African American, even though they comprise more than 14 percent of the U.S. population.

About 90 percent of Habitat for Humanity Portland Region’s homeowners are people of color. The organization is undertaking a renewed commitment with the launching of a Black homeownership initiative to further identify and remove barriers for foundational Black households in the region. Habitat’s plan also includes a commitment to help close the homeownership gap through advocacy and public policy changes in partnership with other nonprofit and likeminded organizations. This is part of a national effort by Habitat, which has been working on this for the past year with resources dedicated to it from a one-time gift from Mackenzie Scott.

The Fair Housing Council’s Allan Lazo served on the Joint Task Force on Addressing Racial Disparities in Homeownership, he is also a member of the Habitat for Humanity Oregon Board of Directors. He says there are both mechanical issues and systemic issues to be addressed before the homeownership gap can be closed. Ultimately, there must be a change of heart.

“It sort of doesn’t matter if there’s enough homes at a price that everybody can afford,” Lazo said. “If somebody is going to be discriminated against buying that home or living in that neighborhood, we also have to clear that problem. I often frame it as not just housing that’s safe and affordable, but also free from discrimination. Otherwise, we continue to lock out the same set of folks who have been denied that opportunity historically.”

Selected Sources:

Oregonian series, “Blueprint for a Slum” from the 1990s:

Buyers say home loans refused for some NE sites, Oregonian, Sept. 10, 1990

Neighborhood activists blame blight on lenders, Oregonian, Sept. 11, 1990

Albina Lawsuit:

Albina history:

Urban Institute research on Black homeownership:

Additional sources:

Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment, 1940-2000 by Karen J. Gibson