Portland, Oregon is known nationally and across the globe as one of the most progressive enclaves in the world. We are a national leader in our commitment to combatting climate change. We boast a strong and vibrant LGBTQ+ community. We pride ourselves on our enlightened tax policies and voter-approved bond measures aimed at combating the wealth gap and spurring civic and cultural engagement. We welcome visitors, shun bigotry, and don’t tolerate hate. What’s less known about Portland is the severe history of racism that, to this day, permeates all systems and institutions, including our neighborhoods, schools, laws, and housing policies.

Portland is, by most measures, the Whitest (big) city in the nation. When Oregon’s Constitution was adopted in 1857, it banned the entrance, property ownership, or residency to any Black person. Yet, during this time, a married White man could receive up to 1,300 acres of land, free of charge, if he chose to settle here. During and after the Civil War, Oregon earned itself a reputation as a White utopia, the same utopia that later Oregonians proudly claimed to have been a “free state.” The truth, as most people of color in the state know, is that Oregon was far from a utopia. It is one of only six states that didn’t ratify the 15th amendment, which formalized Black citizenship and suffrage. The harsh reality is that people of color, particularly Black residents, faced institutionalized discrimination and racial exclusion all the way through the next century.

Nearly fifty years after Oregon became a state, the city of Portland really took shape. Bridges were built, neighborhoods were designed, and parks dedicated. In 1903, city parks and scenic by-ways were implemented under the Olmsted Portland Park plan; 1908 saw the opening of Reed College. Two years later, the Hawthorne Bridge opened for commuters. The city as we know it today stemmed from the early developments at the turn of the century. Unfortunately, so too did the discriminatory housing practices that reverberate to this day.

Though Portland’s Black population accounted for less than 1% of Portland’s makeup for most of the first half of the 20th century, they were steady targets for White-fear and outright violence—effects which found itself manifested in local housing decisions. During this time, entire neighborhoods were zoned for the explicit segregation of races. Government housing officials, local realtors, bankers, appraisers, and landlords all contributed to an especially combative combination of tactics used to drain wealth, spatially and socially distance races, and disproportionally direct public funds to White neighborhoods. There is no clearer example of this than in Portland’s Albina Neighborhood.

The Albina District was officially incorporated into the city in 1891 and was a central location for industry interests of the Union Pacific railroad company. During this time and for several decades, Portland’s Black population lived scattered throughout the city, though many took up housing near the few employers of Black workers, primarily near Union Station. According to research conducted by Dr. Karen Gibson of Portland State University, about half of Portland’s Black residents were homeowners at this time.

Before the Great Depression, Black-owned businesses, though uncommon, were prosperous. The Golden West Hotel on the corner of NW Everett and Broadway thrived in serving Black railway porters, cooks, barbers and waiters working for and near the railroad hub of Union Station. What transpired in the years leading up to WWII signifies the systemic racism that downgraded Black homeownership and relegated an entire population to second-class status.

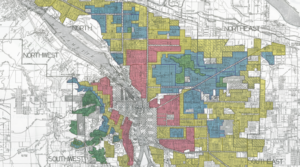

By the mid-1910s, city leaders and local realtors saw the potential economic upside of confining Black residents and people of color to racialized ghettos. According to Gibson, in 1919 the Portland Realty Board “adopted a rule declaring it unethical for an agent to sell property to either Negro or Chinese people in a White neighborhood.” The process, called restrictive covenants, was a legal and widely accepted practice. The policy was also institutionalized in government subsidizing of amenities that disproportionally benefitted White neighborhoods. Parks, roads, fire stations, police, water, electricity, and school investments were prevalent in up-and-coming White neighborhoods in the West Hills, near Mt. Tabor, and in the Alameda area. Today, the generous zoning and abundance of parks and water towers in predominantly White neighborhoods showcase such disparities.

Meanwhile, Portland banks made it policy, in conjunction with realty industry standards, to decline loan requests to Black families applying to mortgage homes anywhere in Portland—except in the area near Williams Avenue in N. Portland’s Albina District. The 1939 training manual for local realtors reflects this reality in stating that they envisioned “setting up certain districts for Negroes and Orientals.”

Meanwhile, Portland banks made it policy, in conjunction with realty industry standards, to decline loan requests to Black families applying to mortgage homes anywhere in Portland—except in the area near Williams Avenue in N. Portland’s Albina District. The 1939 training manual for local realtors reflects this reality in stating that they envisioned “setting up certain districts for Negroes and Orientals.”

In addition to this broader systemic racism—individual racism also fueled the subjugation of people of color into substandard housing. Private landlords during this time often refused to allow Black tenents in their properties outside of Albina. Those that did own properties in the segregated district often overcharged Black residents, required higher deposit thresholds, and employed intimidation tactics to squeeze profits.

In the years between 1910 and 1940, these practices pressed more than half of Portland’s Black population (over 1,900 people) into the underfunded and underdeveloped Albina Neighborhood. The century that followed showed little sign of improvement in city policy and systemic racism. These early years set the stage for further segregation and sanctioned a behavior that led to Portland’s severe housing crisis and alarming homeownership gap for people of color—the effects of which are alive and well today.

– – – – – – – –

This article is part of a series outlining the racist housing practices that have pervaded in Portland’s neighborhoods for over a century. Part two features the policies that led to disaster at Vanport, White flight in North Portland, and the groundwork for the urban renewal projects that desecrated the Black community in the 80s and 90s.

Sources

- Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment, 1940-2000 by Karen J. Gibson

- Building a West Coast Ghetto: African-American Housing in Portland, 1910-1960 By Stuart McElderry

- The Racist History of Portland, the Whitest City in America By Alana Semuels